Life may present you with situations in which anger appears justified. I don’t mean a bureaucratic nightmare or Monday traffic jam. I mean when someone has wronged you without excuse or apology and at no fault of your own. Think of a pickpocketer that takes your wallet and leaves you stranded in a foreign country. Or the loss of a dear friend at the hands of a reckless drunk driver. No one would fault you for resenting the wrongdoer.

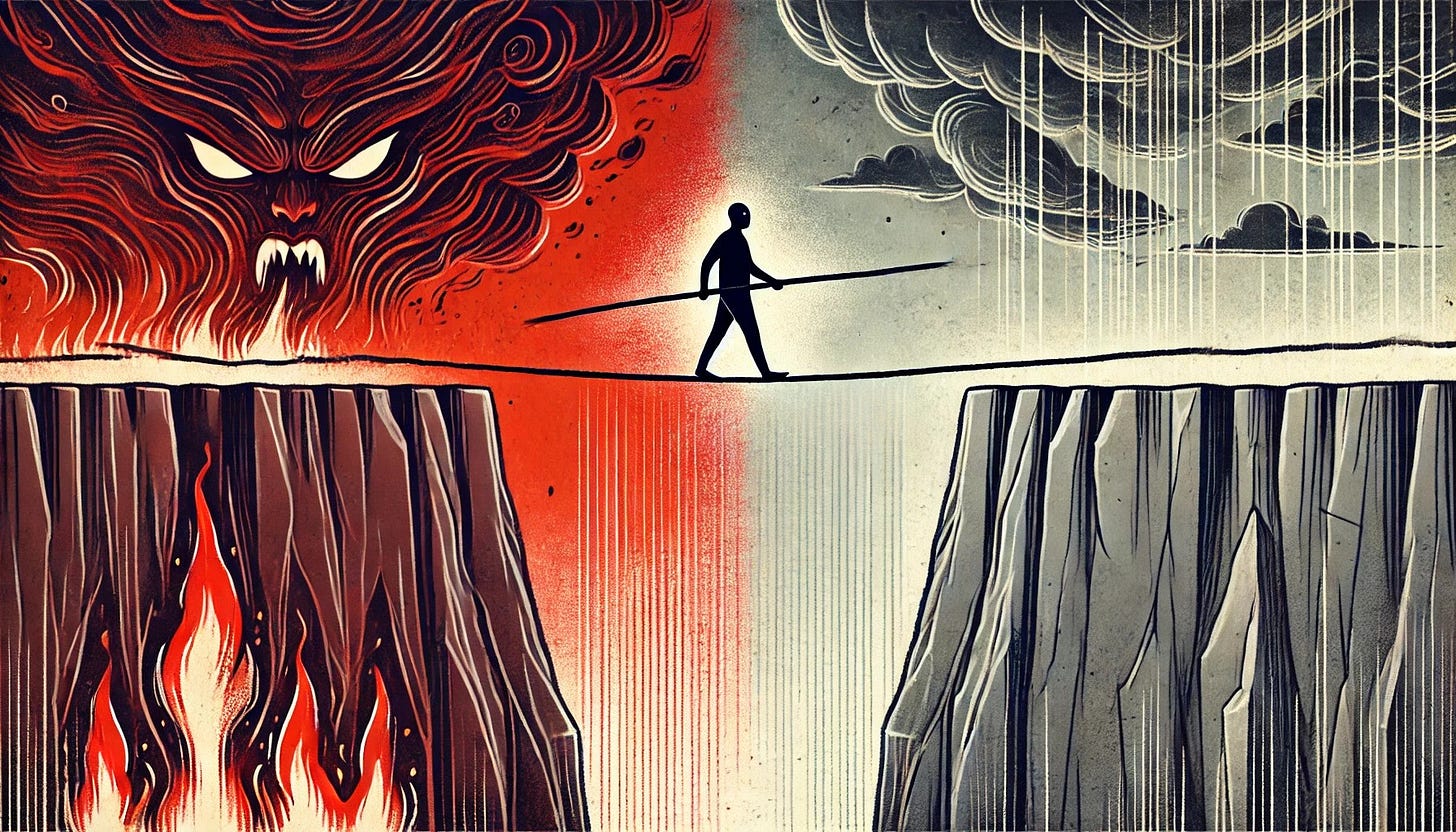

Except maybe the Stoics, whose writers drain inkwells retracing the thin line between anger and passivity that constitutes the virtue of justice. For Massimo Pigliucci, the author of How to Be a Stoic, the answer to the eponymous question is discipline in desire, action, and assent. The last—assent, how we react to situations—amounts to daily recitals of the Serenity Prayer. In the case of our pickpocketer, Pigliucci advises that we recognize the misjudgement of our robber and refrain from the same mistake. That once we see that the fault lies in the wrongdoer, we might

…step back and analyze a situation more rationally, always keeping in mind the dichotomy of control between what is and is not in our power. It is not in our power to make thievery disappear from the world, but it is in our power to engage in a battle of attention with thieves, if we think that’s worth our efforts and time. It is not in our power to change the robber’s judgment that forgoing his integrity in exchange for a lamp or a wallet is a good bargain, but it is in our power to make the reverse judgment ourselves.

It’s easy to admire Stoic serenity. Navigating this path would already be a step towards maturity for most residents of our melodramatic generation. In the eyes of Pigliucci, it gestures towards virtue. But in my vision, the line he straddles strays too far into the side of passitivity.

Let’s demarcate and reflect on the three steps of his instructions. The first is to identify the robber’s misjudgement—that he “must have reckoned that what he was doing was worth the price”; the second is to remind ourselves, in contrast to the robber, of how much we value our own integrity; and finally we are to move on and leave the robber as is. Read in tandem with Martha Nussbaum’s Anger and Forgiveness, you would note that this kind of forgiveness remains tinged by an air of “superiority or vindictiveness.” One hears echoes from the sermon on the mount here. There’s this Christian conservative undercurrent that runs through pop stoicism and you can see in the way they speak about choice, integrity, and responsibility. That you made a bad decision and it’s not my place to stop you rattles me because it’s the same basis for libertarian neglect. I’m better than you and I pity you.

My discomfort stems from my view—a denial—of free will. Consider our pickpocketer. Let’s allow ourselves to speculate on the context of his theft, one that probably involves poverty, involuntary unemployment, and no small amount of apparent moral failure. These in turn might be traced to childhood of neglect in a deprived neighborhood, or discrimination on the basis of race. For our drunk driver, we might struggle to imagine the kinds of misery that might drive someone to severe alcoholism and a total disregard for others. People are products of situation, environment, upbringing, genetics, and a thousand other factors that don’t look like “free will.”

If you can entertain determinism, then consider how it reshapes the moral terrain. If humans are automatons, analogous to pigeons and chatbots, then our conventional notions of responsibility begin to feel unnatural. Someone might be frustrated about windshield guano or a customer service bot from hell, but the emotion wouldn’t take on a moral tinge (“you oughtn’t do that, [pigeon/bot]!”).1 As Robert Sapolsky argues in Determined2, feelings of anger, disappointment, and moral righteousness are just as confused when applied to humans. If you replayed our universal history from the start, it would end again in our pickpocketer committing his theft.3 So there never was a chance for the robber to make the right decision, no room for him to be born into privilege, stumble on just the right teacher, or end up getting a well-paying job after all. Contra Pigliucci: it’s not in the robber’s power to change the robber’s judgment either.

Recovering a Stoic response in this terraformed terrain presents a paradox. It now becomes your responsibility to change the robber’s judgment, or at the very least to try—to practice what Nussbaum terms “unconditional love and generosity”, a visceral urge to care for your wrongdoer free of calculation or judgment, and maybe to provide guidance. You must assume responsibility despite knowing that free will is an illusion. And in doing so you must reverse and radicalize fundamental attribution error4, which is to say: to adopt the belief that your actions are products of your disposition (or virtue or the good will), but others’ are products of their situation (and their upbringing and their genetics and so on). You get the contradictory conclusion that you must take responsibility for others even as you don’t expect them to take responsibility for themselves. And if you squint, a justice weaved from Stoicism and determinism as such looks a lot more like love than pity.

On this point, Strawson Freedom and Resentment might agree. For him, anger, forgiveness, love, and generosity alike are all kinds of “reactive attitudes.” Reactive attitudes, including resentment, are justified expressions of social expectations: I expect you to not steal from me. Strawson suggests that offending actions are indeed expressions of will and carves out exceptions for children, pathology, exceptional circumstance, and so on. Michelle Mason has a great summary of these points. In contrast, I (and Sapolsky, and others) bite the bullet and embrace the “objective attitude”, which is “to cease to regard him as a moral agent.”

Where you can also find a better treatment of determinism and some consequences for moral luck, justice, and so on.

This is the rollback argument for incombatibilism, and you can find a modern, refangged formulation in Todd (2018).

Which raises its own set of challenges for virtue ethics and its derivatives. Harman (1999) suggests we “very confidently attribute character traits to other people in order to explain their behaviour" despite the fact that "there is no evidence that people differ in character traits,” using this to explain and discard theories of virtue. But this doesn’t present a challenge for the Stoic determinist. You might posit and aspire towards (imaginary) traits like wisdom and justice while expecting nothing of the sort in your compatriots.

This is acc so fire. Writing style reminds me of Nassim Talebs

Are you a chef? Because you really cooked here!