Trading Time

Purchase your time wisely.

Authors note (10/9/24): I updated my calculations to include “ad-free premium.” It’s clearly good to buy these services for streaming and Spotify, less clear for YouTube.

The time exchange

There’s a liquid market for your time. It’s open from the moment you wake to the second you fall asleep. Thousands of market makers compete for hundreds of dollars of daily flow. There are rules and regulations, winners and losers. Inefficiencies galore: orders cross all the time. And you might not know it, but you’re the sole customer.1

The time exchange is not an analogy but a homology. Markets for physical goods alongside markets for labor. Employers go out and bid for time (create job openings), workers go out and offer their time (apply to jobs), these orders cross and sometimes a trade happens (“you’re hired!”). The worker can also buy their own time. Shelves are stuffed full of “time-saving products” readily available for purchase. If you’re on autopilot right now, you almost certainly would be better off if you bought or sold some time. Perhaps both.

My basic thesis is that time is fungible. Your time is spent on things you want to do and things you don’t want to do. The former includes hanging with friends to enjoying a bubble bath. The latter looks like working, commuting, waiting in line—banality, ennui, boring shit. This dichotomy permits us to talk about “time” of the first type, time spent doing things you want to do.

The prospectus

You object that…

Quality of time is not dichotomous! Some activities are “just ok”, like shopping or mowing the lawn, which I neither like nor dislike. And even beyond a revised trichotomy, I like or dislike activities in continuous degrees. So you can’t just talk about saving “time” as such.

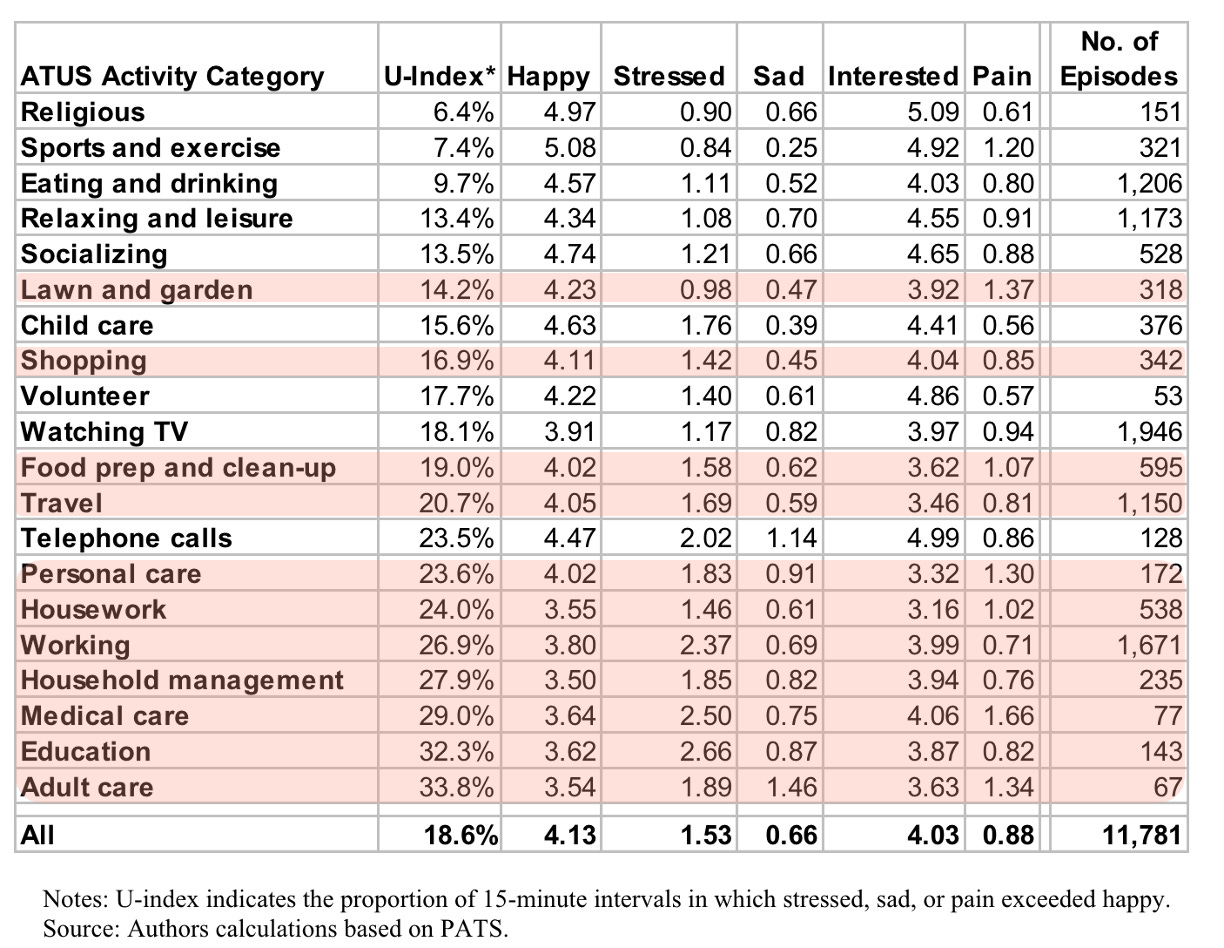

The data suggests a natural dichotomy. Krueger et al. (2009) prod people throughout the day to report what they’re doing and how they’re feeling, giving an estimate of subjective well-being by activity. The resulting table—with “undesirable” activities highlighted in red—are below. You can disagree with me about borderline cases (like shopping or lawn-mowing); if you have a taste for a red activity, then feel free to glaze over those sections below as you’re reading.2 But I doubt most people would pay to do any of the red activities. This is the time I propose to save.

Note that what matters most is that we agree on the red. If all the annoying stuff is about equally bad, then it doesn’t matter much which annoying stuff you’re replacing. You’ll use the additional free time to do the next best thing with your time, which will be unique to you and indifferent to activity you replace. Free time is free time is free time.

If you don’t like this approximation, you can imagine a more granular market for quality-adjusted time, expressed in units of “1 hour of 1 happiness unit.”3 For now, you can hold your nose and mentally adjust all the numbers here by U-index, if you’d like.

You can’t just “sell time.” We’re salaried workers who can’t just clock in an extra hour. Most of us are working eight hours because that’s the only denomination available!

About one-in-six American workers hold gig jobs (e.g. Uber drivers) and another (maybe overlapping) one-in-six work part-time. For them, there’s certainly room to just work more.

But even for the salaried majority, the claim holds if you take it less literally. For one, in most jobs, working longer hours is indirectly beneficial: it can lead to a promotion, raise, or just even just keep you from getting fired. In expectation, you earn more when you work more. Why else would more than half of American workers work overtime?4 And get this: there are other employers! There’s probably a job similar to yours out there that demands more hours (think Tesla or Goldman) and compensates you for it.

The returns to time are sharply diminishing. It’d be nice to get 10 minutes back. But would I really benefit from 4 hours of dilly-dallying? What if I have nothing to do at all and start taking drugs?

Returns to free time should be diminishing if we allocate our free time efficiently. That is, if we keep doing whatever will make us happiest at the margin, we’ll eventually run out of really good uses of our time.5 And the same is true of money! The second million dollar jackpot you win will never be as useful as the first. That’s why my interventions here are on the scale of minutes, and not hours. Convexity leads to modest suggestions.6

Time that you had to begin with isn’t the same as the time you get back. If I spontaneously decide to call in sick. Not only am I kicking myself for losing out on my salary, but I also just won’t have that much to do with the new time. There’s a fallacy here: even if selling time makes us less happy, that doesn’t mean that buying time back will make us happier.

There’s research on this! Professor Ashley V. Whillans at HBS has spent a third of her research career studying whether time savings increase happiness. Sticking just to the titles: she’s found that people are happier when they value time over money, and specifically that buying time promotes happiness. It’s universal: more quality free time predicts happiness among European millionaires and residents of Kenyan slums alike. Case closed!

Now, yes: faced with sudden free time, you might feel guilty or unsure of what to do. But if you intentionally purchase time for yourself with both a sense of ease and a plan in your mind, then you’ll be happier. And even if you don’t premeditate it, you might quickly become accustomed to new recurring time-savings anyway, achieving the same.

If there really is a market for my time, what happens when orders cross? You claim that employers are willing to pay me more for time than various services are charging to save me time. If time really is fungible, then in a real market, there should be trades for them to do! But they don’t. Ergo, there’s no market.

Except trades do happen when the market crosses! You get free lunch at your office because your employer wants to cheaply buy back your commute time, even when you would’ve been unwilling to use Uber eats yourself. Banks comp dinners and Ubers so that people can stay later at the office. Companies regularly pay for C-Suite personal assistants because it’s a cost-effective purchase of chief X officer time. Whenever they can, employers will bypass you to purchase time-savings products on your behalf. Which begs the question—why don’t you treat yourself to more time?7

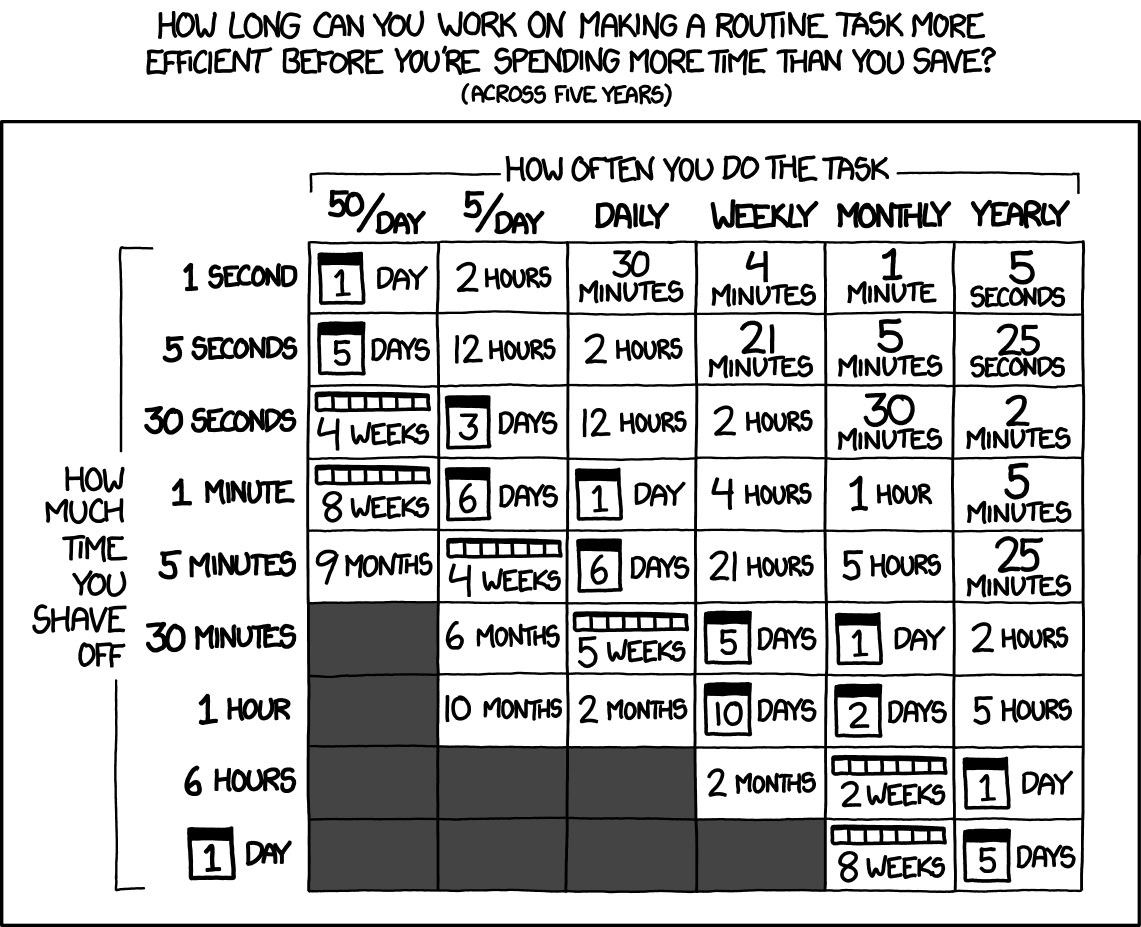

Is this even worth the time put into thinking about it? A lot of these seem like marginal improvements that could take a lot of time to decide on and configure.

It depends, but probably. See chart.

This whole exercise sucks the joy out of time. A la Four Thousand Weeks, we should maybe stop trying to wrestle control over our time and just live in the moment. Obsessing over time efficiency will ruin whatever time you do have.

I want to address the meat of this objection in full another day. But for now, it’s worth differentiating time efficiency (which is about getting more out of your time) and time-money efficiency (which is about discovering Pareto improvements across those buckets). You can “be in the moment” all you want, but it sure would be nicer to spend your moment hanging with friends than alone on the subway.

The order book

As the designated market maker, I aggregated all the offers available for time, including both the size (hours of time for sale) and price (dollars per hour). I calculated the underlying on this spreadsheet using publicly available data. I used myself (or an average American, where relevant) as reference. I took about 5 hours; you should put in at least an hour to make your own version.

Here’s the executive summary:

Invest in a home, not in a ride. Cutting time off your commute is pricey, unless you haven’t picked where to live yet. The premium on an apartment or house closer to your job is way less than what you might pay in Uber and tolls instead. Consider it!

Cook to your means. Meals are a prototypical case. The more you’re willing to pay, the more time is available to save. They’re also the largest item on this list, so it’s really worth optimizing this. I generally think you should only grocery shop and cook if you actually enjoy it a lot.

Get TSA precheck. You should register for TSA precheck if you fly more than 5 times a year. It’s been discussed before elsewhere and I won’t reiterate.8 Clear, however, is not worth getting on top.

If you’re wealthy, leave chores to others. Whenever you’re substituting another human to do your job—for chores or transport—you’re paying about the average national salary. Babysitting might be on the lower end of that, but then again you might not mind taking care of a kid so much. But do your own laundry!

Pay to avoid distractions. If you’re a college student or frequent Internet user, a distraction blocker is a marvelous return on investment, nearly two orders of magnitude better than other products. If a time blocker can effectively even save you 1 minute of time a day from Facebook and Tiktok, you’ve made your money back.

Anything I’m missing? Let me know!

It’s worth closing by proposing a strategy: you should purchase all of the time-savings that cost less than your hourly wage.9 If you buy anything that’s cheaper than your wage, it doesn’t even matter how much your time is “really worth,” because what you could do instead is use all the extra time you get to work more. Concretely, it might look like paying for Ubers to get to work earlier and stay longer. Or you could a distraction blocker so that you can stay focused for longer. It’s pure and literal arbitrage: you don’t need to take an opinion on what your time is worth. And where I work, discovering an arbitrage should prompt you to put on running shorts and sprint to make the trade.

The trading terminology is gratuitous and I apologize. You can find a dictionary here. I want to be forthright that my model of time is bleak and reductive and ruthlessly financialized. It’s also immediately productive and generative. I’m going to give specific and personalized advice on how you can make better trades with your time.

An interesting point can also be made here about self-selection. For borderline/near-neutral activities like gardening, shopping, cooking, people have some discretion choosing how much time to devote (which is, in fact, precisely because there are time-saving products). Since the study weighs each reported episode of an activity equally, those who do that activity more, often voluntarily, are over-representative. So I expect ratings for semi-discretionary “neutral” activities to be biased upwards.

Which retraces the shift from life-years to quality-adjusted life years in public policy. You can find a summary in Spencer et al. (2022), some criticisms in Pettitt et al. (2016), and an example in Vanessa et al. (2020).

You might object here that most people don’t choose to work overtime; that it’s required by the job. I’d argue that this is already part of their decision to take the job. The employee knows that taking this job involves overtime in a way that some other jobs might not. And in effect they decide to work longer hours because they prefer a job with overtime over a hypothetical alternative without. But here’s a paper that disagrees, after considering some of these arguments.

With the caveat that some activities really might have increasing utility in time, to an extent. Working on your side startup or trying to learn guitar might only be worth it if you have more than an hour a day. Freeing up a lot of time unlocks activities that have a high minimum threshold, activities that may turn out to be some of the most meaningful that we can pursue.

This cuts both ways. If the world was linear, then we should expect more extremes. The bourgeoisie should purchase as much time as possible and spend it all working, while the hoi polloi might think that jobs aren’t worth the time and just… not work?

Inevitable complications. Your employer bears the cost of more than your wage. They also pay for your recruiting costs, income taxes, healthcare benefits, and other labor costs. So your wage + prorated labor costs provides a floor for how much value you add to the company, per hour. There may be a wide gap between your wage and your marginal value added to the company, and goods within that price range might be services that your employer will buy, but not you. Asterisks all over.

Reddit absolutely agrees. And the blogger and X influencer Nearcyan points out that the real added benefit is reducing variance in wait times.

So if you earn $15/hour, you might buy a distraction blocker, TSA precheck, and live closer to work.

My friend Neeyanth suggests Brick (https://getbrick.app/shop), an expensive but highly potent distraction blocker

Well-written blog that combines great quantitative analysis, research, and writing, as always! I've been intently reading every single one of these pieces.

I do have a few counterpoints/corrections to make:

1. (correction) "…so if reading Brainpickings can shave even 5 seconds off your day, then you should be willing to tolerate 12 hours worth of spam." Shouldn't it be 2 hours according to the table? (I do gladly read all of Brainpickings still.)

2. (disagreement) "It’s worth closing by proposing a strategy: you should purchase all of the time-savings that cost less than your hourly wage." The major thing I think this post overlooks is that we usually can't convert time to money whenever we want, as you referenced: "Most of us are working eight hours because that’s the only denomination available!" Your refute is that "In expectation, you earn more when you work more;" my objection to this is that returns on this time are also sharply diminishing—extra compensation in food and Ubers is a benefit worth much less than the hourly wage for the workers who get these benefits, and the company is encouraging this overtime because it benefits *them*, not so much their employees as a group.

I once read a showerthought that "If Bill Gates dropped a $100 bill, it wouldn't be worth his time to pick it up." But, as commenters argued, if he picked it up, he would still be $100 richer: He would have earned the same money anyways; much of our earnings are already fixed "in the background." And so because of this, I can only take about half of the proposals you make. 😅

Keep up the great work! I really love how you can quantify and explain parts of life that seem otherwise routine and immutable.